A View of St. Matthew

by Cynthia Cupe

Art History

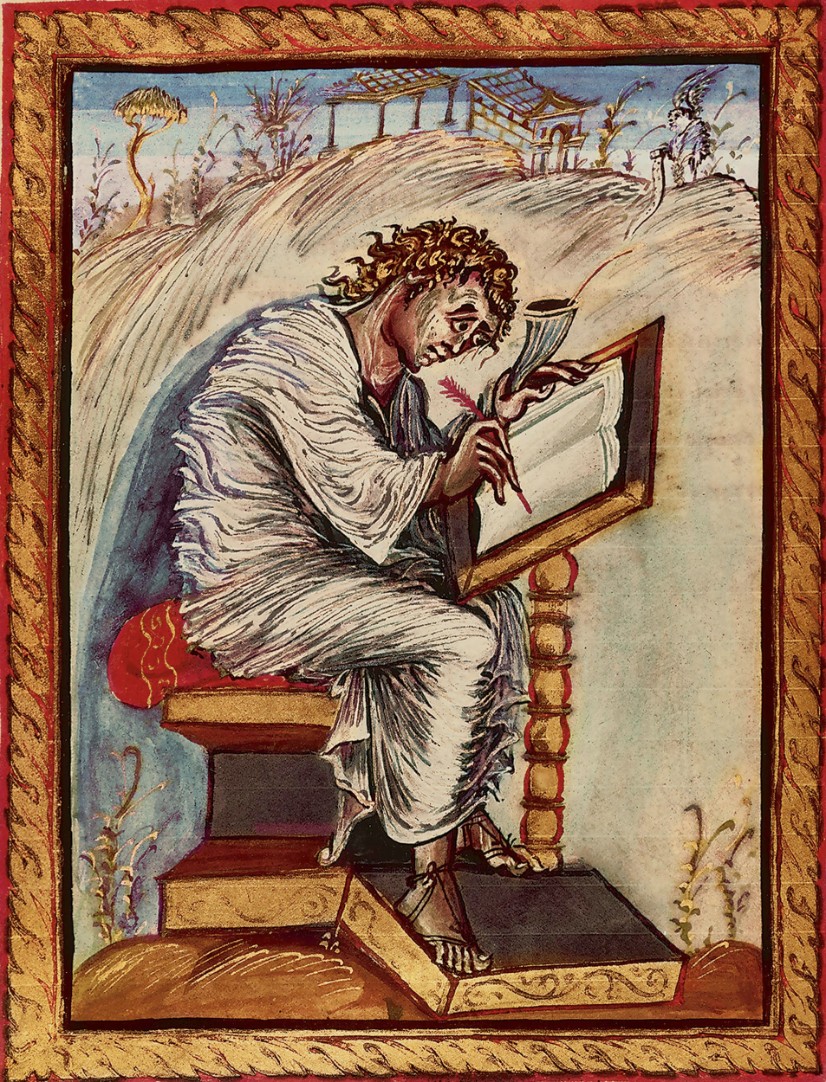

"St. Matthew" from the Gospel of Reims was created in the second quarter of the 9th century 816-841, A.D., in Bibliotheque Municipale, Epernay, France. It was commissioned by Archbishop Ebbo of Reims. The original artist is unknown.

This paper will discuss the method used in creating the art work, provide a detailed visual analysis, and explore its historical and religious background.

The page with St. Matthew from the Ebbo Gospel of Reims is a two dimensional illumination drawn on vellum. The outermost edge of the picture is designed with classical gold colored acanthus leaves which give the impression of traveling flames.

The picture is ten and one-fourth inches in length and eight and one-half inches in width. The artist has used a mixed medium of materials such as ink, water-based paint, and gold.

The expressive qualities of the lines in this picture vary. Some are vertical, wavy, horizontal, thin, thick, diagonal, parallel, and perpendicular. The actual and implied lines are harmoniously merged within the picture plane and space. In addition, the artist has used biomorphic and geometric shapes within the picture plane which provides several perspectives of distinct proportions.

Matthew sits on a solid, gold and brown trimmed, black-colored wooden stool, cushioned by a red pillow that is fashioned with two wavy vertical lines encasing tear shaped drops of gold that bulge from behind him and overlay the stool.

Slightly leaning forward, Matthew clutches a red quill pen in his right hand and an inkhorn in his left hand as it rests upon the codex which is being supported by a music stand-looking type of desk.

The representational style of naturalism in Matthew's facial features and body position evokes the feeling that he is in a panic. Beneath his thick, twisted, black eyebrows, his eager, focused and dispirited eyes protrude from their sockets, encompassed by white, ghostly pale, wrinkled skin on his forehead and cheekbones. The simulated texture demonstrates great technique in the artist's pen and brush strokes.

The expressive qualities of color transmit to the viewer that the artist has become emotionally merged with the task before him through the value and intensity of cool colors blended in the picture space.

A sky-blue to a deep sea-blue shadow emanates from the left side of his body and rear of his neck down to the brown mount of earth beneath him, symbolizing an aura or emotions.

Matthew wears a white Roman-style toga that gives the illusion of scurrying around the form of his body and implies that he is jittery.

The saturation and hue of his golden-brown colored hair, combined with heavy and wavy snake-like patterns of the artist's brush strokes, make his hair appear on edge, too.

Wearing thin strap sandals surrounding his dark-tanned ankles, exposing his toes, his right foot rests at the base of the desk, as his left foot rests slightly higher, near the pole of the desk.

From an atmospheric perspective, tiny structures of trees, plants, bushes, and house frames fill the horizontal landscape in the background that also appears to engage in Matthew's edgy emotions. The downward pen and brush strokes and asymmetrical lines make them clearly unsteady upon the trembling hills. This picture of Matthew depicts a mood of anxiety as he writes his Gospel account.

The artist had good form and very expressive qualities of lines. The composition and choice of colors are true to the Medieval style associated with Reims. Art and sculpture from Reims are known to portray a sense of implied interaction, wavy hair, drapery that drew on classical sources from Rome, swaying figures, and other forms of movement.

Carolingian Art came into being during the second half of the 8th century. Charlemagne, also known as "Charles the Great," transformed the cultural history of northern and central Europe by imposing Christianity throughout his territory. This new-founded institution became known as the Holy Roman Empire after the 13th century (Hartt 282-283).

In an effort to restore the Roman Empire and to revive the arts and education, help was sought from Benedictine monks and nuns. Charlemagne purchased Greek and Latin manuscripts, "solicited foreign scholars especially Alcuin of York, who supervised campaigns aimed at establishing correct texts of the Bible because they had become distorted from constant copying" (Hartt 282).

Books played a major role under the rule of Charlemagne to promote Church law and practice. He ordered that paintings done during his reign were to depict Christ and the Apostles' narratives from the New Testament. Books were written on animal skin- either vellum, fine soft calfskin or parchment, which is heavier and shinier.

The skins for vellum were cleaned, stripped of hair, and scraped to create a smooth surface for the ink and water-based paints. This process required time and experience to prepare and complete. Many pigments had to be imported, especially blues and greens (Stokstad 326).

Medieval books were usually made in a workshop called a scriptorium by the monks and nuns in a monastery. As the demand for books increased, schools of illumination were set up in regions such as Metz, Tours, and the bishoprics of Reims. The scriptorium's main task was to produce authoritative copies of key religious texts. Often work on a book was divided between the scribe who copied the text and one or more artists who did the illustration using gold leaf or gold paint.

Illustrated pages like St. Matthew filled cannon tables to show the corresponding passages in the four Gospels. Every monastic scriptorium developed its own distinctive designs according to local artistic traditions and the books available as models in the library or treasury (Stokstad 251, 318, 325).

In sum, this picture can be perceived as a depiction of St. Matthew being anxious while writing and trying to finish his work or being burdened by what is being revealed to him as he writes. Nonetheless, the page with St. Matthew from the gospel of Reims has been created with high emotional energy.

Works Cited

Hartt, Frederick. "Pre-History Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture," Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prince Hall Inc. 1976, 282-283.

Stokstad, Marilyn. "Art History: A View of the West Vol. 1 3rd Ed." Upper Saddle River, N.J. Pearson Education, Inc. 2008, 251, 318, 325-326.